Water is Life

Also in this edition: The women growing vanilla in Veracruz. Towards a comprehensive plan for agriculture. Paquito D’Rivera: My music will go on as long as people put up with me.

Lea La Jornada Internacional en español aquí.

The scarcity of water: a source of conflict and a weapon of war

Half of the world’s population experienced severe water shortages during at least part of 2023, and in Mexico, one out of every three households does not receive water daily. This month, the discussion in Mexico’s Congress of the first major water law in more than 30 years offers both a diagnosis of the problems and interests at stake, and a long overdue opportunity for reform.

The global numbers are staggering: Of the world’s 8.2 billion people, 2.2 billion lack access to drinking water and another 3.5 billion do not have adequate sanitation services. “If the international water outlook is marked by droughts, floods, and conflicts between nations; by overexploitation and/or control of the resource by economic or social groups, there is yet another very serious issue: its use as a weapon of war,” writes Iván Restrepo.

There is no need to look to other continents to see conflicts over water. In Mexico, there have been more than 300 in the past five years. They range from scarcity in rural and urban areas and contamination, to opposition to hydraulic projects.

Currently, water demand in Mexico exceeds available supply; the agricultural sector by itself consumes 67.5 percent of available water. After the privatization in 1992, the president explained, private interests took over water concessions and today they are able to earn 300 million pesos a year selling water to municipal governments.

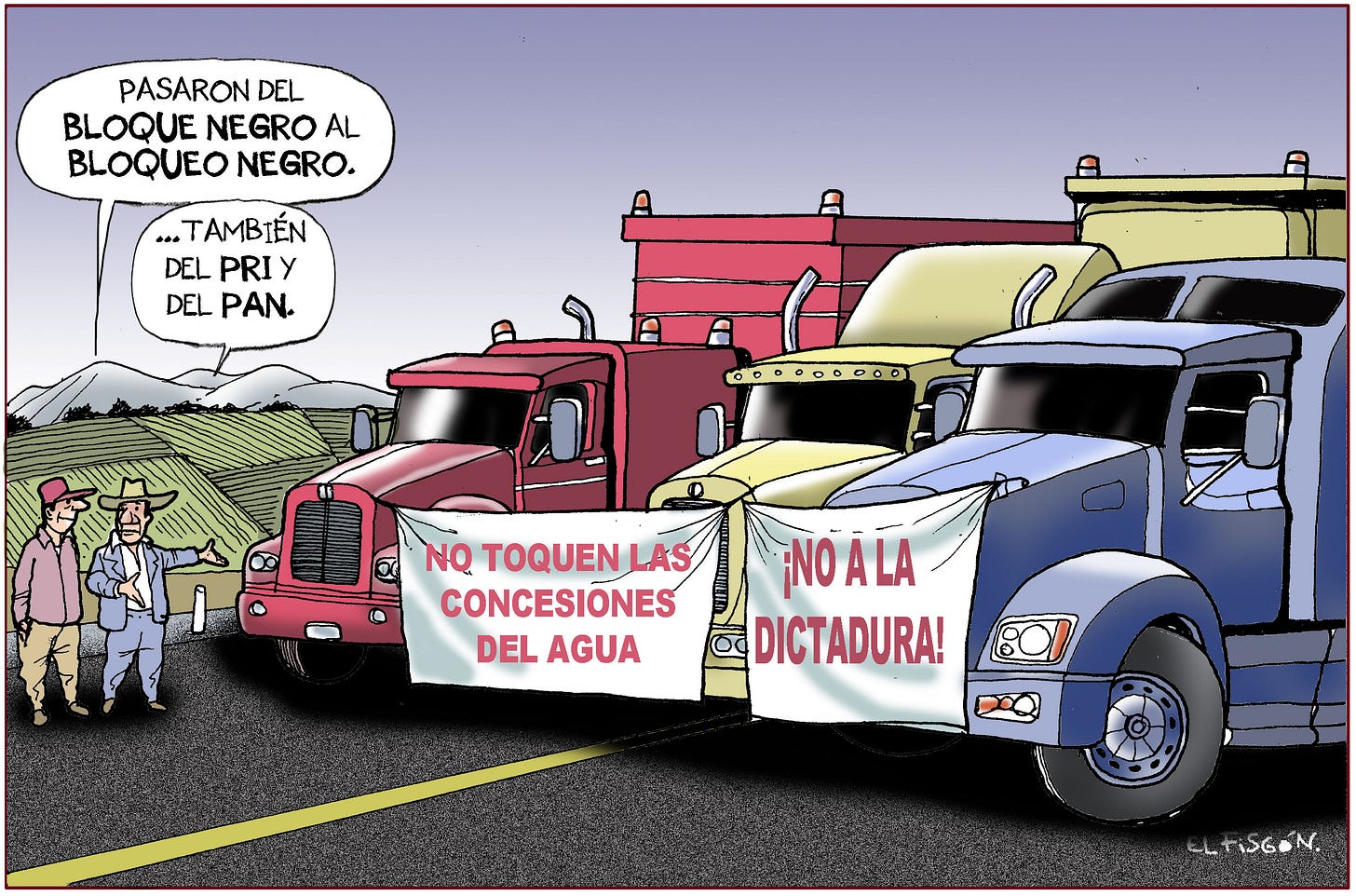

Congress is about to approve a new water law, but balancing the interests of industry, society, and nature isn’t easy. The legislation on water has matured slowly, and the process is complex, requiring input from business groups, industrialists, mining interests, ejido members, communal landholders, and small private landowners. Presidential initiatives for a new General Water Law and changes to the National Water Law have drawn criticism from agricultural producers, experts, and legislators at the start of the forums, as their current wording would allow concessions held by large corporations and banks, such as the one owned by Ricardo Salinas Pliego, to be extended for speculative purposes.

Alfonso Ramírez Cuéllar, deputy coordinator of the ruling Morena party in the Chamber of Deputies, said the goal is water justice and full respect for the concessions and hereditary rights of farmers, as well as preservation of the water-land relationship necessary for food production. “Until we reach a consensus and a final wording, this proposal will not be voted on,” Ramírez promised.

Everyone agrees on the need to rewrite the National Water Law, which opened the door to private permits more than 20 years ago—permits that grew from 2,600 to 360,000 by 2023. But as always, the challenge in water reform lies in the details. Experts welcomed the fact that President Claudia Sheinbaum’s proposal submitted to the lower house mentions the importance of communities in water management and control. Deputy Jonathan Puertos Chimalhua of the Green Party added that Indigenous communities “for centuries have protected” some of the country’s most important water sources, and called for them to be recognized in the new laws, since “there is no better ally for preservation than these communities.”

In Chihuahua, agricultural producers opposed to the new General Water Law met with the PAN-majority state congress. “The main concern isn’t reform itself, but how they want to do it. A bad reform can harm the states, the producers, and the human right to water itself,” explained PRI deputy Guillermo Patricio Ramírez Gutiérrez.

The Quote:

Life sprung from water. The rivers are the blood that nourish the land, and the cells that think for us, the tears that cry for us, and the memory that recalls us as are all made from water.

Memory tells us that today’s deserts were yesterday’s forests, and that the dry world was once a wet one, in that distant time when water and land belonged to no one and to everyone.

-Eduardo Galeano, Del Agua Somos

In Case You Missed It

◻️ The vanilla-growing women of Cuyuxquihui. In the Totonac region of Veracruz, vanilla is not just an orchid: it is a living history symbolizing memory and resistance. Cultivated since pre-Hispanic times by the Totonac people, vanilla has long been a source of identity and livelihood. Yet behind its fragrance are faces often rendered invisible: the women who plant, care for, harvest, and preserve life in the biocultural landscapes of Papantla, reports Juana Victoria Pérez-Vázquez in La Jornada del Campo.

◻️ For a comprehensive plan for agriculture. Farmers and transporters are protesting again in Mexico, fueled by unprecedented levels of grain imports due to the USMCA—and an unreliable trading partner—the treaty’s renegotiation, concerns about water supply, and the fact that intermediaries earn record profits while producers struggle to survive. “It is essential that authorities develop and present a comprehensive plan for rural areas that goes beyond combating poverty and marginalization and instead promotes a development policy that supports medium-scale surplus farmers with credit, crop insurance, and marketing support,” La Jornada writes.

◻️ Citizen brigades defend immigrants in the U.S. Three short, rapid whistles warn that immigration agents are nearby, while three long whistles signal that arrests are underway. These sounds can be heard in New York, Chicago, Charlotte, and Los Angeles, where entire neighborhoods and local residents are organizing immigrant-protection committees.

◻️ Colombia: Interview with Iván Cepeda Castro. The presidential candidate for the Pacto Histórico coalition is betting on continuity with the project begun by Gustavo Petro, but also on “its radicalization in some cases, and the correction and straightening out of things that have gone wrong.” Meanwhile, Petro claims that the United States offered millions of dollars through the IDB to Colombian opposition figures to buy votes.

◻️ Honduras: referendum on change from a model concentrated in 10 families and their networks, to another that, while imperfect, prioritizes historically excluded sectors. On November 30th, Hondurans will vote not only for a presidential candidate, but on whether to continue a national project that, for the first time in decades, has begun to break the economic elite’s historic monopoly over political power.

◻️ More than 600,000 asylum applications in Mexico. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees reports that asylum claims in Mexico have increased more than one hundredfold in a decade: “Once composed mainly of people from northern Central America, it now includes individuals from across the Americas and extracontinental populations with complex and distinct protection needs.” In this context, migration specialists, public sector officials, and multilateral and human rights organizations have called on judges to establish “clear limits” on detaining or expelling people on the move.

◻️ Defending a century of organ grinders. For more than a hundred years, the organ grinder has been part of the soundscape of a Mexico reborn after the Revolution. The original instrument is a wooden box weighing between 24 and 38 kilos, with an internal cylinder, metal pins, and a crank that produces mechanical music. Now traditional organ grinders are fighting to protect their sonic culture against “fake grinders” who use MP3 players with prerecorded music.

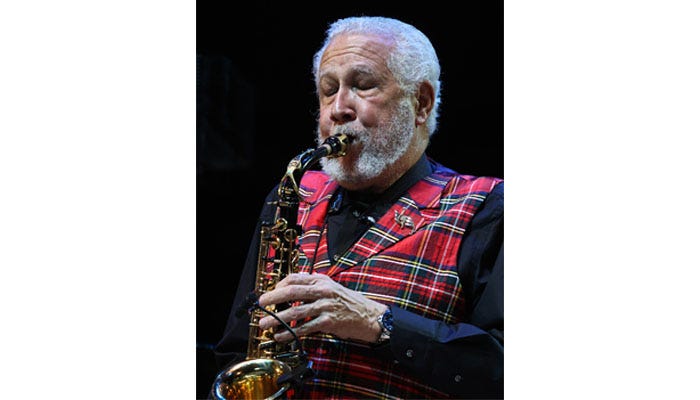

◻️ “My music will go on as long as people put up with me”: Paquito D’Rivera. In good spirits and joking throughout the concert, D’Rivera asked the audience at one point who the most famous composer in history was. When the crowd answered “Mozart,” he replied: “The most significant piece ever written for the clarinet is the A-major concerto by Mozart—whom everyone thinks was Austrian. But Wynton Marsalis told me he was from New Orleans.” He then performed the second movement of the concerto—but as blues.