21 Mar 25 | Changing the Way We Read

Also in this edition: Protests in 23 cities. The solution is in the countryside. El Salvador, Trump's jailer. Dudamel begins his farewell to Los Angeles.

Lea La Jornada Internacional en español aquí.

How to survive catastrophe

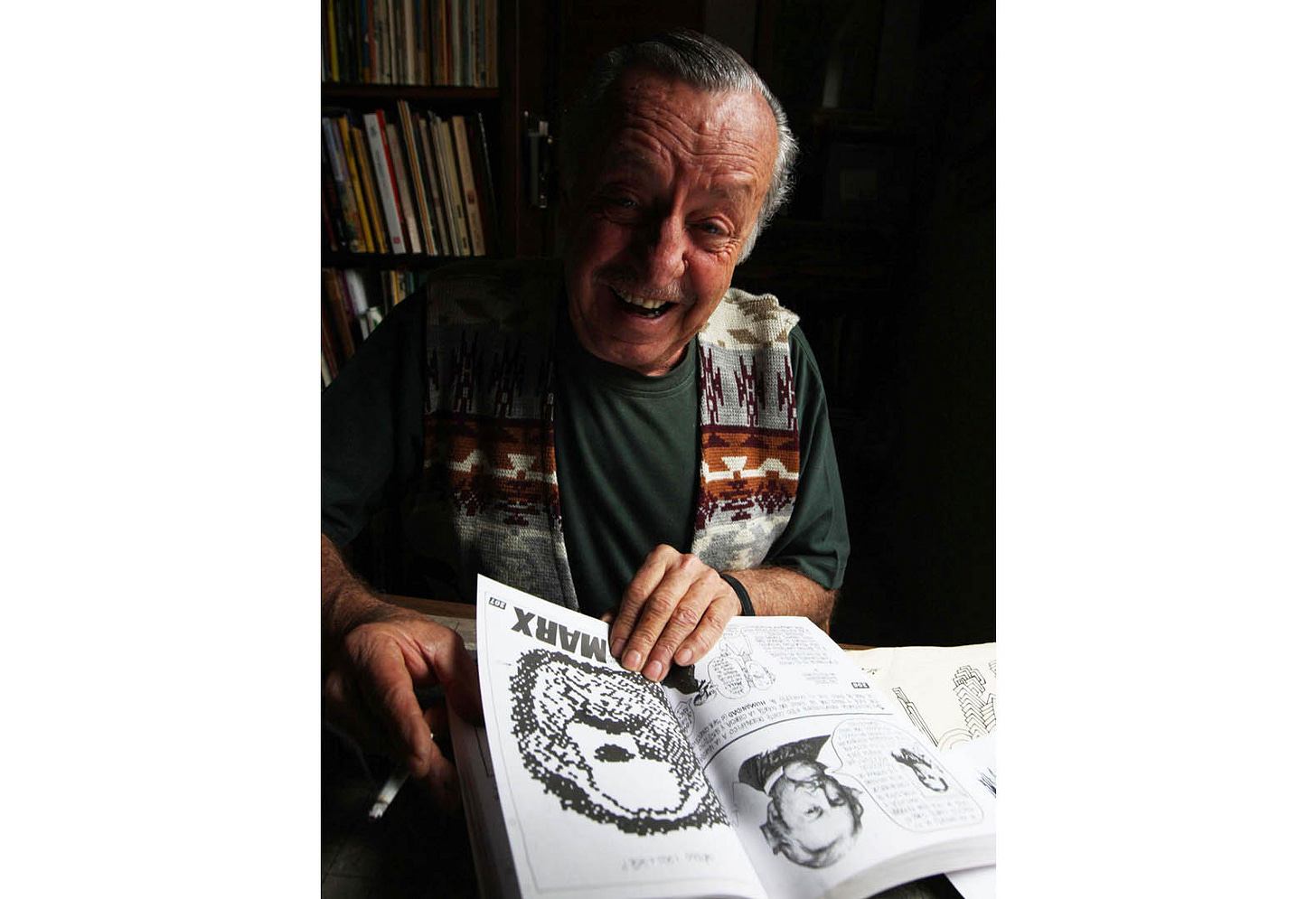

“Humor is the only way to survive this national catastrophe. Without humor, it's very hard not to sink into depression. Not just for me, but for a good part of the population, that's what has saved them, laughing at those who oppress them. It's a kind of revenge,” explained cartoonist Eduardo del Río Rius, when he spoke about the situation in Mexico in 2010– unwittingly offering a guide to surviving the Trump era.

The cartoonist saw humor as a way to lighten the “fucked-up reality” of Mexicans. “Without humor, I don't know where our people would go. The only revenge we Mexicans have is to laugh at the powerful who are fucking us over, and without that, our people would have disappeared; we would be just another star on the glorious gringo flag.”

Inside the gringos’ own country, Rius’ words resonate, and his peers like Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, and John Oliver, are key to confronting Trumpism, just as the great Egyptian comedian Bassem Youssef is key to confronting the genocide in Gaza. In their best moments, they try to do what Rius did: not just mock the oppressors, but inform like journalists and raise awareness like teachers.

Rius passed away in 2017, but his wisdom and humor continue to educate generations of people in Mexico and around the world. He remains the mentor of Mexican cartoonists, including those at this newspaper, such as El Fisgón, Helguera, Hernández, and Rocha, who continue his legacy and that of other great cartoonists. “I'm convinced that almost every Mexican has a Rius book at home. He changed the way we read in Mexico,” commented cartoonist Rafael Barajas, known as El Fisgón. With his 130 books of cartoons, Rius inspired a new genre of educational comics, especially through the series “Para principiantes/For Beginners,” all part of what can be called the “Rius phenomenon.”

▶️ VIDEO: Cartoonists talk about Rius’ legacy in this video and in this one.

Rius began his brilliant career as a cartoonist in the middle of the cultural cold war of the fifties, which would make him a prized jewel sought after by capitalists and socialists alike. Imperialism attempted to co-opt him in 1959. The government of Mexican President Adolfo López Mateos awarded him the National Journalism Prize, and the United States embassy invited him on an all-expenses-paid trip to explore their country in the company of a CIA agent. That trip, instead of convincing Rius of the glories of capitalism, strengthened his political conviction and gave him the chance to see Fidel Castro, who was visiting the U.S. after the triumph of the Cuban revolution.

The idea of making educational books came to Rius while writing his famous comic strip, "Los supermachos." When he no longer had material to complete his comic, he once explained, he borrowed from the novel and began teaching classes on topics he considered of general interest, such as socialism, nutrition, unions, historical figures, and religion—it was an invitation to question everything, even God.

The entire history of Christianity has been a great farce, Rius insisted. We’ve still got enough time to say, Let me think for myself. Don't cram my brain with things I don't know. Ignorance is the mother of all religions. Rius claimed that the point of his life was to turn people into atheists, vegetarians, and leftists.

The author of Marx for Beginners, Cuba for Beginners, Drugs: the Big Business of the United States, and ABChe never stopped asking questions, even about those revolutions and radical changes that failed to live up to what they claimed were their leftist principles. In other words, he refused orthodoxy - the point was to ask questions, be critical, and laugh at illegitimate power, whatever it may be.

In 2010, Rius confirmed that he wasn't ashamed to confess that he was still a man of the left, even though he no longer believed in the same things he used to, like killing all those sons of bitches who have been taking us for fools.

One of the last Rius cartoons that La Jornada published in 2014 sadly remains relevant today.

The Quote

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out– because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out– because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out– because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me– and there was no one left to speak out for me.

—Martin Niemöller

In case you missed it

◻️ The horror at the Izaguirre ranch is not an isolated event. The gruesome discovery in Jalisco of 400 shoes, clothing, and human remains led to protests in 23 cities. President Claudia Sheinbaum expressed solidarity with the families of the victims of forced disappearances and assured them that there will be no impunity or coverup. La Jornada underscored the urgency of the actions announced by the federal government to end forced disappearances in Mexico.

◻️ The solution lies in the countryside. La Jornada del Campo publishes a report on a possible alternative to the agroindustrial model in the Yucatán Peninsula. This report is particularly important in the context of the failure of what Carlos Fernández-Vega describes as the terrifying outcome of Carlos Salinas de Gortari's efforts to reform the ejido system of small landholdings for rural people and La Jornada's investigation into the land grabbing that had led to 36 people owning more than 39,000 hectares in high-value tourist areas, forests, and jungles.

◻️ Farmworkers in Mexico. Thousands of farmworkers in San Quintín, Baja California—mostly Indigenous Mixtecs from Oaxaca and Guerrero—have managed to improve their working conditions, thanks to their organizing efforts over the past 10 years. But these improvements are insufficient considering how this community of 50,000 have historically been left behind. For a more comprehensive report on farmworkers in Mexico, check out La Jornada del Campo.

◻️ The beginning of the end of the Russia-Ukraine war? Our correspondent in Moscow, Juan Pablo Duch, writes about the first step toward a ceasefire on energy infrastructure that was announced after a lengthy telephone conversation between Putin and Trump.

◻️ Resistance and constitutional crisis in the US. Little by little, popular resistance against Trump and his policies is building in the United States, first among immigrants, students, civil rights advocates, and a few national and local politicians. At the same time, the confrontation between the executive branch and judges is intensifying, bringing the country to the brink of a constitutional crisis.

◻️ El Salvador, Trump’s jailer. In exchange for a few million dollars, President Nayib Bukele has become a jailer for the United States. The business agreement between the two governments is a violation of the human rights of these migrants. La Jornada writes in an editorial that this arrangement should be investigated by the United Nations and democratic governments around the world and repudiated.

◻️ Two islands, “two wings...” Precisely for daring to defy power and placing solidarity at its core, Cuba remains under attack. It is “the threat of the good example,” writes Tanalis Padilla. In Mexico, that solidarity continues to save the lives of the most vulnerable. Meanwhile, Bad Bunny’s latest album shares the sound and the story of Puerto Rico's struggle and lament.

◻️ Dudamel begins his farewell to Los Angeles, celebrates El Sistema, and prepares for New York. The last half-century, he wrote, has transformed Abreu's vision into a global movement that has brought music to millions of children. "Play, sing, and fight forever... Music heals the social sphere, because it instills sensitivity and respect for others. It transforms the audience, but you transform yourself in unison," the musician explained.

📚 What we are reading

Michael Moore, on the wife of the Palestinian student from Columbia University who Trump is trying to deport.

Did you receive this email from another reader?

Sign up here to receive La Jornada Internacional in your inbox. It’s free.